The Mess Age

We need to talk about what we talk about when we talk about talking about popular things

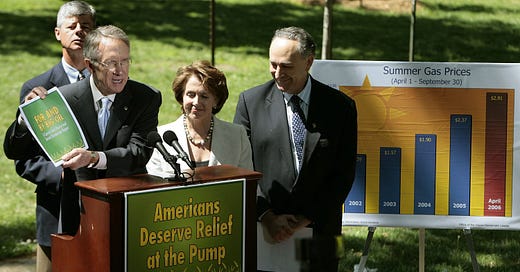

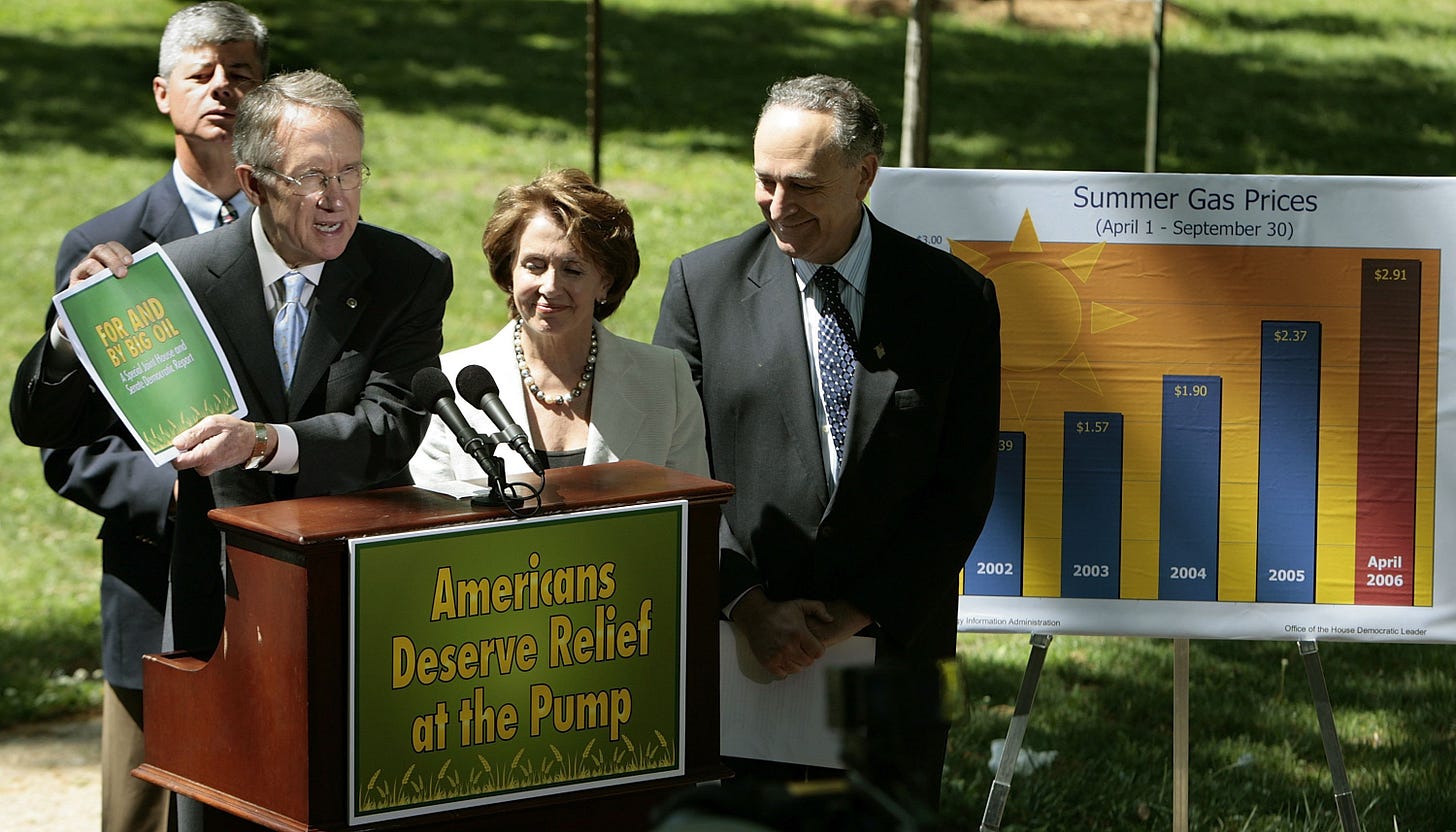

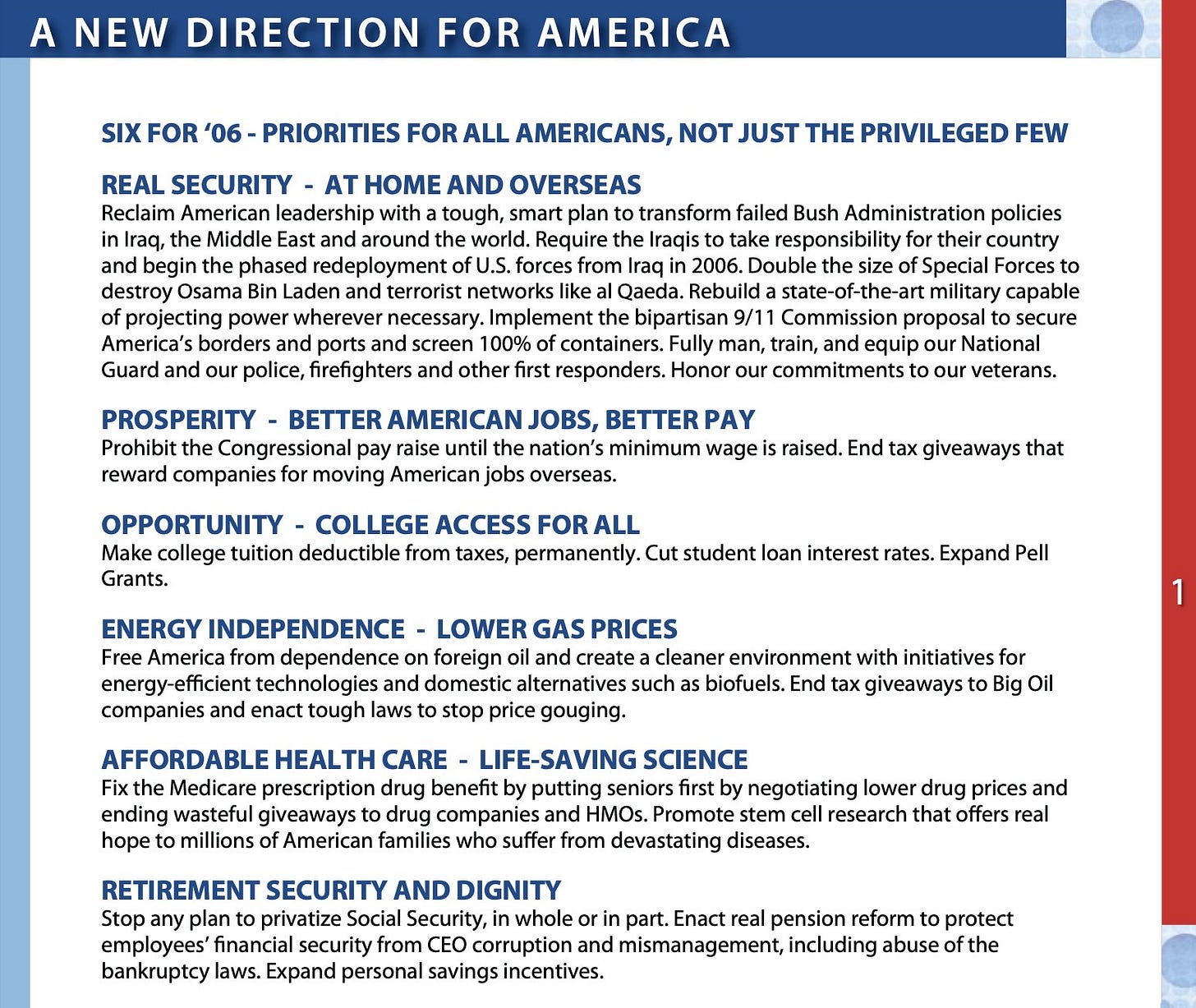

Matt Yglesias, a newsletter author, spent time this past weekend sending around, for some reason, a list of campaign proposals the Democratic Party ran on in the 2006 midterm elections. This seemed to be part of a broader argument that Democrats now are worse at crafting winning messages than Democrats then. As you may recall, Democrats did quite well in the 2006 midterms and then won the presidency in 2008. The general idea is that these are the sorts of things Democrats used to say, and then they’d win elections, but now they only say things college-educated activists like to hear, so they lose elections. Thus, they should go back to saying the things they said in 2006.

One issue with this argument is that, if you do recall the 2006 midterms, you will understand that it’s deeply silly to attribute the results to this Democratic messaging and even sillier to claim that a return to this messaging would lead to similarly sized victories. For one thing, as David Dayen pointed out, it is probably not very politically effective to promise to lower drug prices in every election but then not actually do it every time you win power.

The other issue is that Democratic messaging had very little to do with the actual political situation in 2006. By 2005, Americans were evenly divided on whether the invasion of Iraq (which had been massively popular a few years earlier) had been a mistake. By October of 2006, Pew was saying stuff like this: “There is more dismay about how the U.S. military effort in Iraq is going than at any point since the war began more than three years ago. And the war is the dominant concern among the majority of voters who say they will be thinking about national issues, rather than local issues, when they cast their ballot for Congress this fall.”

Even if you can’t attribute it to one specific thing like Iraq (or Bush’s stupid social security privatization scheme, or Hurricane Katrina in late 2005, or the Mark Foley page scandal in September 2006, or any of the other things people covering politics were actually focused on during this time—the actual news), all of those things added up to create a condition in which Democrats were running against an increasingly unpopular president from a party widely considered to be corrupt and incompetent.

This is not a takedown of Matt Yglesias or an attempted demolition of some random half-baked thing he tweeted, nor is it meant to be my final word on the epic debate of our time on Doing Popular Things or Saying Popular Things or Rejecting Wokeism. This is just an attempt to clarify what I think these arguments are actually about.

Running against an unpopular president remains a good way to pick up seats in Congress no matter what your message is, and that’s just what the Democrats did again in 2018. The problem is the margins were smaller than 2006, and, unlike Bush, Donald Trump’s unpopularity seemed eerily stable and entirely disconnected from actual events. Now, everyone with a brain expects Democrats to lose Congress in the next few years, and perhaps the White House again as well, which is why everyone is yelling at each other online all day about messaging and popularity.

Faced with this depressing vision of the near future, it is obviously understandable to say, “Well, the Democrats should go back to doing what worked in 2006, when they could win statewide elections in places like Missouri and Ohio, because they clearly stopped doing something that worked then, or started doing something that doesn’t work since then.”

So Democrats could recruit more white moderates maybe. It is true that the Democratic Party used to have a lot more white moderates, or at least white people coded as moderate, who could win elections in the sorts of places that also supported George W. Bush. They have less of them now, which makes it much harder for the Democratic Party to win control of Congress. There are a lot of reasons for the decline of these sorts of politicians. One reason is that many of these white moderates subsequently lost elections to Republicans. A proposal to reverse that trend that I do not think should be taken seriously—though it’s one that I fear would be quite popular in the offices of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee—is “make it 2006 again by science or magic.”

Here’s my suggestion: Perhaps the Democratic Party has, actually, stayed more or less the same. (Notably, many the people running it today were also running it in 2006.) Perhaps the Democratic Party largely stood still, leaning heavily on policy and messaging very much like the document pictured above, as everything else changed.

A fun fact—one that might seem almost unbelievable to any longtime follower of American politics—is that many white American voters did not associate the Democratic Party with racial justice issues until the Obama presidency.

Here's how the political scientist Michael Tesler explains it:

Across time, a large and stable majority of whites with a college degree believed that the Democrat was more supportive of federal aid to blacks. But among whites with no college degree, there was a substantial 22-point increase in awareness from 2004 to 2012. The election of an African American Democratic president helped shrink a different diploma divide — this time, in awareness of the two parties’ differing positions on race.

Whites without diplomas (not necessarily "working class" whites, of course) abandoned the Democratic Party years before Donald Trump descended the escalator and a solid decade before anyone who works for a think tank had ever encountered the slang form of the word “woke.” “Simply put,” Tesler says, “racially resentful whites without a college degree were most likely to flee the Democratic Party during Obama’s presidency.”

To me, the evidence suggests this was less of a result of Democrats going “too far” on these issues than it was simply that this particular segment of white voters finally and decisively noticed (or, rather, had it explained to them, over and over again) that the Democrats are the party “for” Black people. One might even trace the shift to the day, in July 2009, that Barack Obama said “the Cambridge police acted stupidly” when they arrested Henry Louis Gates, Jr., at his own home.

Those who stress the importance of messaging would identify Obama’s comments as a gaffe. Instead of saying that the cops acted stupidly, Barack Obama should've said, "I have no opinion about this and I'm going to lower the price of prescription drugs." And, sure, maybe that's true. Empty platitudes about race from Democratic politicians do more to harm their political chances than they do to help race relations seems like a defensible and even benign claim. But I think it’s important to be clear that if it hadn’t been this, it would’ve just been something else. Another moment in the Obama years that raised the “salience” of racial justice issues in a way that probably drove more of these voters away from the Democratic Party was when a minor Black government official told a story about helping a white farmer save his farm. Does the political and media environment that created the Shirley Sherrod incident seem like one in which Democrats can simply avoid controversial rhetoric about race?

Democrats who came of age when the party still relied on these lost white votes took some time to process that the loss was not some temporary aberration. But they’re clearly well aware now. Events like the humiliating defeat of Evan Bayh in the 2016 Indiana Senate race surely helped drive home the lesson that “the business-friendly moderate” was no longer a viable model for winning the sorts of very white places that people like Evan Bayh used to win. That worrying realization led inexorably to this modern freakout against rampant liberal activist wokeism dooming the Democrats. And that freakout also reflects a touching hope that 2006 can, in fact, be reconstituted, and it can be done by punching left.

Something I didn’t mention in my recap of the various disasters and fuck-ups that made many smart people believe in late 2008 that George W. Bush had destroyed the GOP for an entire generation, is that he, along with prominent Republicans in Congress like Sen. John McCain, spent his entire second term trying (and failing) to pass something called “comprehensive immigration reform,” which, in most of its incarnations, would have paired additional “enforcement” with some path to legal residency for America’s scores of undocumented residents. It is inordinately clear in hindsight that this contributed immensely to the Republican Party’s unpopularity among hardline conservatives and the future base of Trump’s support. Even as nativism surged in the conservative grassroots, the elites resisted it—for a time. As the oft-repeated story goes, some Republicans decided after their 2012 loss that the party needed to soften its rhetoric on immigration. Instead, a blatant xenophobe shockingly won the nomination, and then the presidency, with a motto about building a border wall.

I bring this up because I think the GOP’s open embrace of nativism was the other crucial key to how we got here—how that Obama-era realignment got fully baked in—and because I don’t think anyone with an argument that Democratic losses among these voters are mainly self-inflicted, due to a stupid embrace of DEI politics, has a convincing argument for how their preferred approach could’ve stopped this nativist push from working so well.

The Biden administration is, in fact, currently testing a sort of popularist approach to immigration politics: They are, basically, not talking about it, at all, while also aggressively cracking down on border enforcement. What that looks like in practice is a Washington Post piece about border arrests being at an all-time high that explicitly frames that as a political problem for Joe Biden’s administration. That fact that “U.S. authorities detained more than 1.7 million migrants along the Mexico border during the 2021 fiscal year that ended in September, and arrests by the Border Patrol soared to the highest levels ever recorded” is not even treated as a crackdown; it’s reported as a Biden crisis his administration can’t get under control. As the Post says: “Border enforcement has become a major political liability for Biden, and the president’s handling of immigration remains his worst-polling issue.”

How could the White House’s attempt to get the border “under control,” in order to reduce the salience of anti-immigration sentiment in our politics, backfire so spectacularly? The same way Shirley Sherrod’s heartwarming story about tolerance turned into a days-long feeding frenzy invoking ancient American tropes about Blacks with government power using it to exact retribution on whites who oppressed them: Because your political opponents also have the ability to craft messages and they are frankly much better at getting those messages delivered to voters. No one has a natural, unmediated opinion on whether or not their country has a “border crisis.” The cannier side understands that politics is getting them to think that there is one, not to make them forget that they think so.

The Post also, quite a bit further down the page, gives one reason that number of border arrests might be so high. The Biden administration is arresting people, sending them back across the border, and then arresting them again when they cross again, as part of its tough-on-migration policy that is having the practical effect of making arrest numbers soar while the president’s popularity wanes and Republicans make political hay out of the number of arrests that the Biden administration is doing at the border. Needless to say, this approach is also demoralizing pro-immigration activists and basically pleasing no one. (The actual popularist move, it seems to me, might be to say you are cracking down on immigration while also disbanding the entire border security apparatus, to avoid damaging news stories about how out of control the border is based entirely on how many encounters border-crossers have with our militarized immigration forces.)

The solution to all this won’t be to lower the salience of “race” and “immigration,” because none of us, Democratic politicians very much included, has the power to do that. Democrats can run on ethanol and lowering prescription drug prices forever—as plenty of others have said, this is what they are already trying to do. And Republicans will run ads about Democrats allowing migrant caravans full of terrorists into elementary schools no matter what is actually happening in the world.

Two things happened in this century that brought us to this point: The conservative movement and Republican Party openly embraced uncut nativism, and voters firmly began conceiving of Democrats as the party for minorities. Some people believe Democrats could negate that first fact and reverse the second. I believe almost every approach to doing either would be both morally reprehensible and pathetically ineffective.

It seems self-evidently absurd to me to believe that enforcing stricter message discipline on all left-of-center people (an impossible thing anyway!) would be sufficient to reverse a generational political realignment—even if Democrats do actually need to find a way to win many of these voters back if they wish to maintain power in our current political system. That is what all these arguments are about: How do we win back these racists? Do we actually need these racists? Are they actually racist or are they mad about the economy? Did being mad about the economy make them racist? Can we make them not racist? Can we make their racism less “salient” to their political activities than other factors?

Unfortunately, the right combination of magic words seems unlikely to put this genie back in its bottle. I suspect the political consultant David Shor would mostly agree with all this, too, except that his income requires convincing Democratic campaigns that he will help them find the magic words.

I started writing a piece on these trends a few years ago, but never finished it, in part because one of the rules of the sort of opinion writing I was doing is that you’re supposed to have some hint of a prescription, something you want someone to do, but it turned out that I simply don’t think the currently constituted Democratic Party is capable of reversing these effects, and I don’t have any good ideas for them that don’t involve overthrowing a system that they’re plainly wedded to. There was some glimmer of hope, this year, that the party’s factions might find some common ground in a mission to rejuvenate organized labor—some elements in the Biden wing of the party finally noticed how its decline coincided with the decline of Democratic fortunes much more directly than did the rise of Critical Race Theory—but (just as in 2009-10) those plans seem unlikely to survive contact with our wretched Senate or our captured judiciary. In such an environment, it must be pleasant to imagine that the way forward is to write “make college tuition tax-deductible” on a campaign website.